23. Januar 2022

Auf Socialnet (21.1.2022) wird der von mir verfasste Einführungsband »Digitale Transformation« (2021, UTB/transcript) wie folgt besprochen:

»Was mich besonders beeindruckt hat, ist die Behandlung der digitalen Transformation innerhalb der geschichtlichen Entwicklung. Dabei scheut sich der Autor nicht, auf die auf diesem Feld viel zu wenig beachtete Antike genauso hinzuweisen wie auf die Prozesse der Entstehung der kapitalistischen Gesellschaft im 19. Jahrhundert und andere historische bis in die Gegenwart reichende Entwicklungen. Natürlich bleibt die Gegenwart der Transformation dabei im Vordergrund der durchweg lehrreichen Ausführungen. Durch den Ausflug in die ältere und jüngste Geschichte werden jedoch die gegenwärtigen Prozesse der gesellschaftlichen und technischen Umwandlung besonders eindrucksvoll beleuchtet und begründet. Viele Befürchtungen und Wünsche, die mit der Transformation verbunden werden, werden dadurch relativiert und verlieren ein wenig an beängstigender Kraft. […] Die Lektüre dieses Buches kann ich nur empfehlen. Wer sein Wissen über die Digitale Transformation erweitern möchte, der sollte seinen Buchhändler stante pede aufsuchen.«

29. November 2021

Auf Soziopolis (29.11.2021) bespricht Jonathan Kropf den von mir verfassten Einführungsband »Digitale Transformation« (2021, UTB/transcript) wie folgt:

»Im öffentlichen wie im sozialwissenschaftlichen Diskurs über Digitalisierung finden sich zahlreiche Disruptionsnarrative: Buzzwords wie Web 2.0, Big Data oder künstliche Intelligenz wollen jeweils einen epochalen Umbruch markieren. Es ist vor diesem Hintergrund so bemerkenswert wie angenehm, dass das jüngste Buch von Jan-Felix Schrape die Digitalisierung eben ›nicht als disruptive[n] Bruch […], sondern als inkrementelle[n] Veränderungsprozess‹ (S. 81) perspektiviert. Digitale Transformation […] versteht sich dabei in erster Linie als Lehrbuch und Einführung (S. 12 f.), ist darüber hinaus aber auch Forschenden zu empfehlen, die sich mit Fragen der Digitalisierung beschäftigen und sich einen flüssig zu lesenden und aktuellen Überblick wünschen.

[…] In der Gesamtschau sind das gewissenhafte Vorgehen und die differenzierte Argumentation des Autors hervorzuheben. Schrape betont durchgängig die Ambivalenz der beschriebenen Entwicklungen. Mal schlage das Pendel stärker in Richtung einer Erweiterung und Ermöglichung von Handlungsoptionen, Kreativität und Spontanität aus, mal schwinge es eher in Richtung einer vermehrten Strukturierung und sozialen Kontrolle. Zudem ist durchweg seine Skepsis gegenüber geschichtsvergessenen Erzählungen erkennbar, etwa wenn er betont, dass die Digitalisierung viele bereits bestehende Trends im Bereich der Arbeit lediglich verstärkt, nicht aber hervorgebracht hat (vgl. S. 101–105).

Den Kapiteln ist anzumerken, dass der Autor zu den jeweiligen Themen bereits seit einigen Jahren regelmäßig publiziert. Entsprechend klar und fundiert fällt die Darstellung aus […]. So lässt sich zusammenfassend konstatieren, dass der Band erkennbar von den Vorarbeiten und der Forschungsperspektive des Autors geprägt ist. Die Darstellung von Forschungsfeld und -gegenstand weist damit einen leichten Bias auf; ich möchte das Buch Lernenden und Lehrenden der Soziologie trotzdem empfehlen, kann es ihnen doch als gleichzeitig historisch informierter und aktueller Einstieg in das Thema der digitalen Transformation nützlich sein. Hilfreich dabei ist insbesondere die übersichtliche Gestaltung, unterstützt durch einen klaren Aufbau, zahlreiche Abbildungen und Tabellen sowie stichwortartige Zusammenfassungen am Seitenrand […].«

25. August 2021

In der Reihe Stuttgarter Beiträge zur Organisations- und Innovationssoziologie ist das Diskussionspapier »Platformization, Pluralization, Synthetization. Public Communication in the Digital Age« erschienen:

The platformization of communication architectures is accompanied by a diversification of individual media use and an erosion of clear structural boundaries between different streams of public exchange. Nevertheless, it is by now evident that the digital transformation does not lead to a general loss of relevance of journalistic services or mass-received content per se and that selection thresholds remain in public communication despite increased connectivity. Against this backdrop, this paper argues that it is still instructive to describe the negotiation of public visibility as a multi-level process, which is now essentially shaped by the peculiarities of digital platforms: First, it examines the increasing platform orientation in media diffusion. Second, it discusses the associated diversification of individual media repertoires and the pluralization of public exchange. Then, the paper elaborates on three basic levels of public communication characterized by a heterogenous interplay of social and technical structuring services.

3. April 2021

Der Band »Digitaler Strukturwandel der Öffentlichkeit« (hg. von Mark Eisenegger, Marlis Prinzing, Patrik Ettinger und Roger Blum) zum 15. Mediensymposium ist erschienen. Darin findet sich auch mein Beitrag »Irritationsgestaltung in der Plattformöffentlichkeit«. Abstract:

Der Beitrag beschäftigt sich mit der Frage, welche veränderten Irritationspotenziale für zivilgesellschaftliche Initiativen mit der digitalen Transformation der Gesellschaft verbunden sind. Der erste Abschnitt diskutiert die sich wandelnden soziotechnischen Infrastrukturen der öffentlichen Kommunikation. Der zweite Abschnitt beleuchtet anhand empirischer Fallskizzen, welche Problemstellungen der zivilgesellschaftlichen Irritationsgestaltung sich in diesem veränderten Umfeld unkomplizierter überwinden lassen und welche Probleme neu entstehen. Daran anknüpfend expliziert der Beitrag die These, dass trotz des medientechnischen Infrastrukturwandels basale Selektionsschwellen in der gesellschaftlichen Gegenwartsbeschreibung erhalten bleiben, deren Überwindung ein hohes Maß an kommunikativer Persistenz verlangt.

3. November 2020

Der Band »Arbeit in der Data Society« (Hg. von Verena Bader und Stephan Kaiser) ist erschienen. Darin findet sich auch der Beitrag »Neue Formen kollaborativer Herstellung und Entwicklung – eine orientierende Typologie«. Abstract:

Im Kontext der digitalen Transformation der Gesellschaft rücken […] neue Spielarten der offenen wie partizipativen Zusammenarbeit in den Aufmerksamkeitsbereich der sozialwissenschaftlichen Forschung. Vor diesem Hintergrund nimmt der vorliegende Beitrag die hierzulande bislang beobachtbaren Ausprägungen kollaborativer Herstellung und Entwicklung materieller Güter in den Blick: Nach einer historischen Einordnung erfolgt eine typologisierende Vermessung des Feldes, in der die sehr unterschiedlich ausgerichteten Spielarten offener Werkstätten und Labs entlang ihrer Ziele, ihrer Koordinationsformen sowie ihrer Finanzierungsweisen voneinander abgegrenzt werden. Daran anknüpfend werden mit diesen neuen Kollaborationsformen einhergehende Potenziale und Risiken diskutiert.

18. Juni 2020

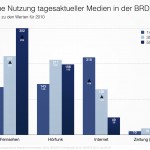

Der Reuters Institute Digital News Report 2020 ist erschienen und bietet wie in den Jahren zuvor einen Überblick zur weltweiten Rezeption von Nachrichtenangeboten und Nutzung der unterschiedlichen Medienkanäle in der individuellen Versorgung mit tagesaktuellen Informationen. Erhoben worden sind die Daten größtenteils Anfang des Jahres – also noch bevor COVID-19 ein weltweites Thema wurde; allerdings wurden einige ergänzende Aktualisierungen vorgenommen. Hier die wichtigsten Links dazu:

4. April 2020

Nachdem letzte Woche die Digitalisierung der Gesellschaft im Zeichen der Corona-Krise im Fokus stand, dokumentiert dieser Beitrag nun sozialwissenschaftliche Diagnosen und Einschätzungen zu der massenmedialen Berichterstattung im Kontext der Pandemie. Denn die zentrale Bedeutung journalistischer Massenmedien in der gesellschaftlichen Gegenwartsbeschreibung, die wiederum Grundlage kollektiv bindender Entscheidungen ist, trat in den letzten Wochen erneut pointiert hervor. Einige auffindbare soziologische bzw. medienwissenschaftliche Stimmen dazu:

Weiterlesen »